Archives

Contribute

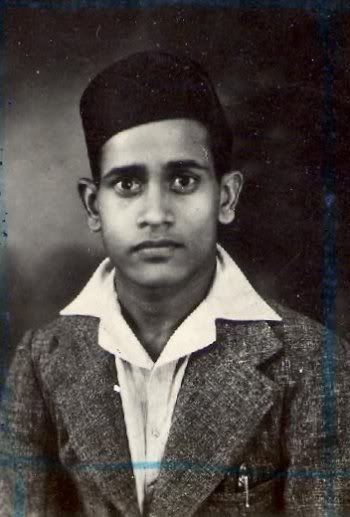

| Bhimsen Joshi, 1922-2011. R.I.P. |

Warren Sanders

02/02/2011

At 8 AM on Monday the great Hindustani vocalist Bhimsen Joshi died in Sayahadri Hospital in his home city of Pune. He was 89, and a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday. One of the most celebrated musicians of the twentieth century, Pandit Joshi was known as an impassioned and technically brilliant singer whose voice could execute anything that came to his mercurial and visionary imagination. His renditions of the traditional ragas of Hindustani music were filled with unexpected twists and turns, and he excelled at the expression of emotional nuance; his uniquely recognizable voice seemed to have its own built-in echo chamber. His last public performance was in 2007, sixty-six years after his stage debut at age 19. Originally from a small town in Karnataka state, he ran away from home at age eleven, searching for music. In 1933, the 11-year-old Pt. Joshi left Dharwad for Bijapur to find a master and learn music. With the help of money lent by his co-passengers in the train Bhimsen reached Dharwar first and later went to Pune. Later he moved to Gwalior and got into Madhava Music School, a school run by Maharajas of Gwalior, with the help of famous Sarod player Utd. Hafiz Ali Khan. He traveled for three years around North India, including in Delhi, Kolkata, Gwalior, Lucknow and Rampur, trying to find a good guru.[6] Eventually, his father succeeded in tracking him down in Jalandar and brought young Bhimsen back home. In 1936 he began his study with Pt. Rambhau Kundgolkar, popularly known as “Sawai Gandharvaâ€. His fellow student at the time was a young woman who became known as Gangubai Hangal, who died last year at 97; I wrote about it here. This concert was in 1957. A young Bhimsen Joshi performs the afternoon raga Multani in a concert in the Punjab. His preternatural virtuosity is evident throughout; the fast melismatic runs called taans are incredibly rapid and superbly articulated. It was around 1977 that I heard him sing for the first time. A musical acquaintance came to visit; after looking through my record collection he said, “I have some stuff you’ve got to hear.†Two days later he brought over three lp records that are still part of my collection. One was a 1967 recording of Pandit Bhimsen Joshi singing ragas Marwa and Komal-Re-Asavari-Todi. I honestly didn’t know what the hell I was hearing, but I was transfixed. Nobody, anywhere, had ever sounded like that. This guy was doing things that great jazz players were doing, only more so. It was obvious that he was a master improviser; his imagination was clearly teetering on the thin edge of madness, even to me, an American kid knowing nothing of the music beyond a few Ravi Shankar records. In the peak of his performing years, Bhimsenji gave as many as 4-500 concerts every year, spending an extraordinary amount of time on airplanes shuttling from one city to another. These were not short concerts, either; a full-length program of Hindustani music often runs 3-4 hours. Audiences were drawn in by his extraordinary vocal range and fervent expression; he also became known for the extravagant gestures and facial expressions which accompanied his wilder flights of imagination — watch the short clip below and you’ll see what I mean. A fast composition “Mohammad Shah Rangile†(in praise of one of the great royal patrons of Hindustani music). This song is in the rainy-season raga Miyan ki Malhar, and many of the words contain images of the monsoons. This concert recording comes from 1971, when a middle-aged Bhimsenji was at the peak of his fame. Through much of his performing career he struggled with alcoholism, which sometimes marred his concerts; it was not until the late 1970s that he was able to sustain sobriety. In 1982 I found out he was coming to perform in Boston, at Harvard University. There had been a few other programs of khyal singing presented there, but this was the first that had me ticking off the days on my calendar. By that time I’d been listening to his music for five years, with growing fascination: how could he do those virtuosic things with his voice? — and how could he think of them? When the night finally came, I sat on the floor of Harvard’s Hilles Library. In front of me was a solid line of neatly dressed Indians, the men wearing suits and ties, the women in saris. I heard people chatting; some were worried that “Bhimsenji†might have been drinking. The crowd was overwhelmingly Indian, with a few Westerners scattered here and there. The M.C. came out and introduced the musicians, and told us we were to hear an evening raga, Shuddh Kalyan. First, playing tambouras, Shubhada Joshi and Madhav Gudi, Bhimsen’s daughter and disciple respectively. Then Nana Muley on the tabla and Purushottam Wallawalkar on harmonium, and finally, Bhimsen Joshi himself. I was quivering with excitement. In years to come I would hear Bhimsenji sing this raga dozens of times, but this was a beginning. When he finally took his place, cross-legged in front of the microphone, the two tambouras started making drones. He sang a few soft, slow phrases — we all seemed to relax a bit. Then he did something: a swift, half-swallowed curving shape that settled on the sixth below the tonic. I was jolted out of my reverie, for the whole front row of onlookers cut loose with a volley of spoken comments: “wah! wah!†and “bahut achchha!†I knew about this behavior, about these phrases — according to custom, a good listener was expected to pay uninterrupted attention to the music and reward the performer with approbatory murmurs. As I say, I knew about this behavior, but this was the first time I’d ever really seen it happening. And, just as I wanted desperately to be able to make my singing voice move “like that,†right then I knew: I wanted to sit in the front row and voice my approval as the music progressed. I remained where I was that night, three or four rows back. Bhimsen Joshi sang transcendently, and the audience went with him. By then I’d been studying Indian music for five years, and I knew enough to follow some of what he was doing; occasionally I too burst forth in spoken applause. At the interval an American friend came up. “Hey,†he said, “let’s go and meet Bhimsen.†“Really? Where is he?†“He’s sitting in that room over there.†I looked in the door, and sure enough, India’s most famous khyal singer was gazing blankly off into space, drawing deeply on a bidi. He looked impressively abstracted; everything about him suggested a man who wished to be left alone. I did. It would be three years before we met. The second half of the concert was even better. The accompanists were responsive and supportive, and Bhimsenji himself soared through the notes of the massively dignified raga known as Darbari Kanada, sometimes known as “the raga of kings.†At one point he began improvising in sargam (Indian solfege) syllables, and a call-and-response emerged with Madhav Gudi, who repeated his phrases in a melismatic open vowel. I went home that night in a kind of haze; it felt as if my whole body was humming, charged with the drone and the moving melodic gestures I’d heard. The composition “Tiratha ko sub karen†(Everybody goes on pilgrimages) in the raga Tilak Kamod. This is a good example of Bhimsen’s singing in the mature style of the mid-1980s. In 1984 I wrote to Bhimsenji, saying that I wanted to learn music from him. He eventually responded, and after a little back and forth correspondence agreed to accept me as a student. Based on this I was able to get a Fellowship from the Council for International Exchange of Scholars, and I arrived in Pune in September of 1985. Over the next year and a half I went to the Joshi residence almost every day; I would practice in a small outbuilding behind the main house. Bhimsenji, however, was not the teacher I needed. The requirements of a foreign student were very different, and while he was a performer of the very highest order, he was an indifferent teacher. (It was not until April of 1986 that I met S.G. Devasthali, who became my guru in the Hindustani tradition and taught me the music I now sing and teach professionally) I was frustrated by my learning situation, but on the other hand, I was part of his entourage, and I got to go to lots of concerts. Lots of concerts. Bhimsenji sometimes invited me to his out-of-town programs, and I’d ride in the back of his big 1963 Mercedes. Once we drove south into Karnataka, where he was to sing in a musical gathering honoring his own guru, Sawai Gandharva. That wasn’t his original name. “Sawai†literally means “one-and-a-quarterâ€; “gandharva†is a divine musician, a celestial singer. The connotation of these two honorifics in conjunction suggests “a celestial singer — plus a little bit more,†and it refers to his abilities in singing Marathi theater songs as well as those of the khyal tradition. His real name was Rambhau Kundgolkar; the kar suffix indicates his family’s home was in the village of Kundgol, which was where we were going. Almost the whole family went along, and the air-conditioning kept us pleasantly cool. As we went further and further south, we moved off the main highway, and the roads got narrower, dustier and bumpier. Twin plumes of red dust rose up behind us. Their conversation was mostly in Marathi, but every so often they’d feel inclusive, and switch to English for a while. Once over the Karnataka border, we stopped by the roadside; they bought some fresh figs and we stood around, eating the fresh fruit and stretching. I don’t remember anything ever tasting as sweet. They played Antakshari, a game based on their shared repertoire of Hindi film songs. Someone would sing a few lines and stop abruptly; immediately, the next player’d have to recall another. Rhythm and melody weren’t factors; success hinged on a different element: to be appropriate, the new song’s first phoneme had to match the ending phoneme of the one before. Rather generously, they included me — even though I knew no Hindi film songs at all. Looking for a way to contribute, I dredged up standards, Appalachian ballads, and all the songs I could remember from summer-camp. Perhaps forty minutes or an hour went by. I’d hear the others, in order, start five separate Hindi songs, each singing a few lines; suddenly realizing it was my turn, I’d contribute a few lines of Pete Seeger, Jerome Kern or Doc Watson. Now, looking back at this after several decades, I can’t help laughing — it was such a perfect microcosm of my whole ongoing struggle with Indian phonetic systems, and of the intersection of two utterly different ways of hearing and understanding sound. Antakshari — a compound of ant (â€endingâ€) and akshar (â€syllableâ€) — or a game remotely like it, could never have emerged from America’s linguistic soil. Whatever the virtues of American English, there is nothing in the training of our ears, minds and tongues to parallel the rich repertoire of phonetic differentiations which are inevitably part of growing up in an Indian-language environment . Bhimsenji himself didn’t join the fun (that would have been interesting, but he was focused on driving, and didn’t say much). I cannot even imagine what he thought when I countered an old Lata Mangeshkar hit with the first few lines of “John Riley.†Eventually we reached Kundgol, where a full night’s worth of music was getting underway. Most of the singers and instrumentalists were junior artists — each took forty-five minutes to an hour before relinquishing the platform. Bhimsenji, as was appropriate for both his seniority and fame, sang last; the night was drawing to a close when he started his khyal in the dawn raga, Lalit. I don’t remember much about how he sang, but I do recall our conversation afterwards. Impressed by his vigorous improvisations, I asked him: “Panditji, you have been driving for sixteen hours, and then waiting to go on stage for the whole night. How can you sing with so much energy?†“Just before singing,†he answered, “I took a bath, and then I ate a hot, fresh chappati.†So that was his secret. I remember nothing of the trip home. We left about nine-thirty in the morning, an hour after Bhimsenji’s last notes, and it was two am by the time we reached Pune. My apartment was a few miles beyond the Joshi residence, and as we came to their neighborhood he said “I am too much tired. You please take a rickshaw.†When he pulled the Mercedes up to his local rickshaw stand, though, the only drivers were sleeping and refused to take me, so he made the extra few minutes’ drive and left me outside my building; the chowkidar sleepily got up and opened the gate, and I went upstairs to bed. The next morning I slept late; a vacation from practicing. When my mother heard him in concert (she was visiting me in India) she commented afterward that the only vocalist she’d ever heard sing with similar power was Paul Robeson. ============================================================================ In addition to his performances of classical music, he was known for singing devotional songs, including the lyrics of medieval Indian saints like Kabir, Surdas and Mirabai, the prayerful Marathi songs called Abhangs, and religious lyrics in his mother tongue, Kannada. In 1985 his was the first voice to be heard in a government-sponsored video on the theme of National Integration. Mile Sur Mera Tumhara made him known to a generation of music listeners more likely to be attuned to Western pop music than to the older traditional forms. The song’s lyrics are unique; One phrase, repeated in fourteen Indian languages: “MilÄ“ sur mÄ“rÄ tumhÄrÄ, tÅ sur banÄ“ hamÄrÄâ€, meaning “When my musical note and your musical note merge, it becomes our musical noteâ€. Wiki He began to experience failing health. In 1999 he had a brain tumor removed, and, surprisingly, began to sing with renewed vigor. A spine operation in 2005 left him paralyzed from the waist down, but still able to sing. His last concert appearance was at the 2007 Sawai Gandharva festival, an annual event held in Pune and celebrating the legacy of his guru. Last week his body began to fail, and he was rushed to the hospital. And now he’s gone. Bhimsen Joshi, 1922-2011. R.I.P.

Bhimsen Joshi as a teenager.

Singing Raga Yaman Kalyan in New Delhi, 1985

1963, with the great Sheigh Dawood Khan on tabla, singing a slow composition in the beautiful morning raga Todi.

In concert in Pune, 1986.

A commercial recording of a devotional song composed by the medieval Indian saint/poet Kabir. “Beet gaye din bhajan bina†(the day has passed without prayer). Bhimsen Joshi’s performances of devotional songs remain very popular throughout India.

A Bhajan in praise of Maa Sharada, an incarnation of Durga. “Sharada†is also a name for Sarasvati, the presiding deity of learning and music, in which case her iconography is considerably less gruesome.

His widest popularity is in the state of Maharashtra. Although originally from Karnataka, he has lived in the Maharashtrian city of Pune for decades, and his renditions of “abhangs†(religious songs in the Marathi language) are hugely popular.

Raga Yaman Kalyan, recorded in 2005. He can no longer cross his legs in the traditional position, so he sings seated on a platform. The accompanying vocalist is his son Srinivas, whom I remember as an affable teenager.

You may also access this article through our web-site http://www.lokvani.com/